September 26, 2016 - March 1, 2017

The Brinton Museum presents William Henry Jackson: Pioneer Photographer of the American West, featuring a selection of historically important 19th century photographs. Perhaps the most famous, and highly-regarded, of the 19th century photographers to photograph the great American West, artist and Civil War veteran William Henry Jackson started his impressive photographic career in Omaha, Nebraska in 1867. In this period, he photographed the Osages, Otoes, Pawnees, Winnebagoes and Omahas. In 1869, he worked for the Union Pacific Railroad documenting the construction of the transcontinental line and the majestic scenery along its route.

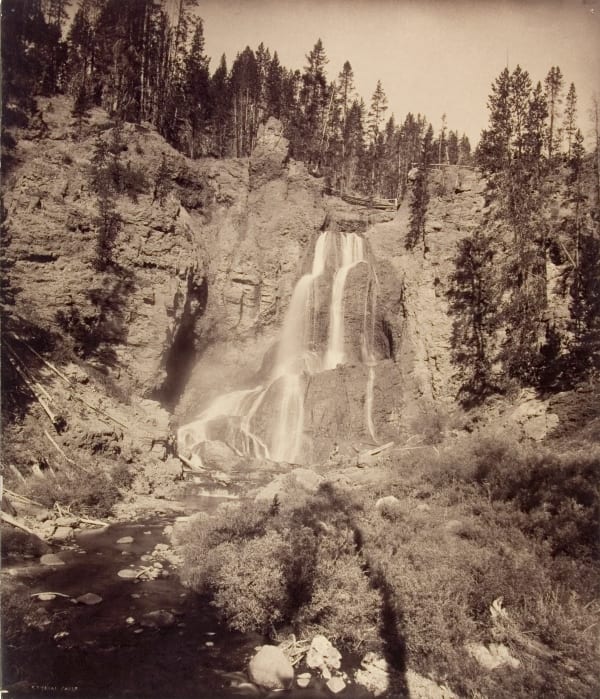

In 1870, he joined the U.S. government survey, led by the American geologist Ferdinand Vanderveer Hayden, photographing the beautiful Yellowstone River region and Rocky Mountains. He continued with Hayden’s 1871 Geological Survey, and followed with Hayden through his last survey of 1878. Jackson’s magnificent photographs along with the works of the American painter, Thomas Moran, who was also a member of the 1871 Geological Survey team, contributed to the establishment by Congress of Yellowstone National Park in 1872. William Henry Jackson: Pioneer Photographer of the American West includes more than thirty-five historic photographs comprised of official survey material, large format landscapes, vignettes and late color work.

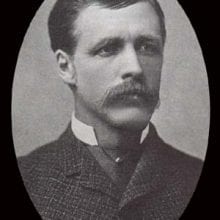

William Henry Jackson

William Henry Jackson

William Henry Jackson (1843 - 1942)

Perhaps the most famous of all the great Western photographers, the artist and Civil War veteran William Henry Jackson (1843 – 1942) started his photographic career in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1867. In this period he photographed the Osages, Otoes, Pawnees, Winnebagoes, and Omahas. In 1869, he worked for the Union Pacific Railroad documenting the construction of the transcontinental line and the resplendent scenery along its route. He joined the 1870 U.S. government survey, led by Ferdinand Vanderveer Hayden, of the Yellowstone River and Rocky Mountains, and continued with Hayden’s 1871 Geological Survey. He befriended the American painter Thomas Moran, who was also a member of the Hayden expedition. Jackson and Moran worked closely together to document the beautiful Yellowstone region. Moran’s paintings and Jackson’s magnificent photographs contributed to the establishment by Congress of Yellowstone National Park in 1872.

Jackson often traveled with three cameras: one to make stereoscope cards; a “medium size” 8×10-inch format; and a “mammoth plate” 20×24-inch camera. The rugged terrain of the West presented enormous logistical and artistic challenges. Jackson had to carry all his photographic equipment: large cameras and heavy tripods, glass plates, bottled chemicals and numerous trays, all of which were loaded on the backs of pack mules. On one such expedition in the scenic Rocky Mountains, Jackson lost a month’s worth of completed negatives when a mule lost its footing and fell.

Jackson continued through Hayden’s last survey, of 1878, when the expedition departed from Cheyenne and travelled through the Wind River Mountains to northwestern Wyoming Territory and into Yellowstone Park. Following the Hayden expeditions, Jackson established his own business in Denver, producing photographs for the railroads, tourists, and collectors.

The last phase of his career began in 1897, when Jackson sold his vast stock of negatives to the Detroit Publishing Company and then was hired as president of the company. In this new role, Jackson oversaw the production and popular sale of a vast number of photographs of both American and foreign subjects. These included color prints made by the new “photochrom” technique—a photographic variation on the chromolithographic process of the era. Jackson lived to the age of 99, surviving all of his fellow photographers of the “golden age” of nineteenth-century Western photography. Recognized as one of the oldest Civil War veterans, he was buried in Arlington Cemetery in 1942.

“Photography was introduced in 1839 by inventors in both France (Jacques Louis Mande Daguerre) and England (William Henry Fox Talbot). From its earliest years, the camera was used in exploration. In the American West, this history is particularly rich, a result, in part, of the inclusion of a photographer in all of the major U.S. government-sponsored Western surveys after the Civil War. Through most of this period, photographers used the “wet-collodion” process—which meant that they had to travel with a portable darktent to coat, sensitize, and then develop each negative on the spot. It could take up to an hour to get a single finished negative. There was very little enlarging in this period: almost all the prints you see here were made by “contact” from negatives of the same size. As a result, field cameras usually ranged from about 8×10 inches in format up to 20×24 inches.

Barabara McNab

Curator of Exhibitions, The Brinton Museum